Growing up geeky

April 13, 2012 1 Comment

On March 26, a piece called “Dear Fake Geek Girls: Please Go Away” appeared on the Forbes Web site. It excoriates those who adopt the “geek” mantle frivolously or as a positive descriptor to get attention.

Over the next couple days, The Internet at large (and other columnists at Forbes itself) came down hard on the sentiment, proclaiming geek culture to be open, welcoming, and delighted to be moving ever more into the mainstream. We’re the cool kids now! Everyone wants to be like us! How could that be bad?

I find myself fairly sympathetic to the original author, Tara Tiger Brown. I’m not sure my feelings are entirely rational, noble, or even healthy, but I’m also somewhat resentful of the way the term “geek” gets thrown around. The exact definition of “geek” is hard to pin down, despite the best efforts of diagrams and cartoons. Brown is correct when she says, “The definition of ‘geek’ is so broad now that it is meaningless.” And a clause earlier in that same paragraph gets to the heart of the resentment: “a term once used to inflict social cruelty is now a term of endearment.”

Social cruelty. For many geeks, dorks, nerds, and dweebs, it’s not our set of interests that define our geekdom; it’s the ostracization we experience. Whether we have these interests and are marginalized because of them or we’re already socially inept and turn to geeky pursuits to entertain ourselves alone, it’s being pushed aside and feeling like we’re always separate from the mainstream world that makes us geeks.

To say that geek is becoming mainstream, then, is a complete paradox. Some of the common interests that geeks share are becoming mainstream, certainly, because technology and marketing have caught up to them. Comic book movies are blockbusters. Cell phones are more powerful than the computers some of us built from kits. Kindles and Nooks let people read – for fun! – with a nifty gadget.

Do I still feel marginalized? Sure. Every time there’s a comic, game or sci-fi convention, my Twitter feed overflows with ecstatic fans posting photos of attendees in costume, the celebrities they meet, and previews of the next big release. Some of these events are too far away to be practical, but this past weekend was PAX East, an hour from my home. I even knew people going, but while I enjoy them, I’m just not that into games. I’d feel as fraudulent as I secretly find the folks flashing their TARDIS iPhone cases without having a clue what Bessie or a Zero Room are.

As a kid, I was into Star Trek. Really into it. My first memory from a movie theater is asking my mom what the caption at the end of Star Trek III (“And the adventure continues…”) meant. I dressed as Geordi LaForge on Halloween in fourth grade. And yes, I attended conventions – not in costume, but wearing fannish T-shirts, pins and hats.

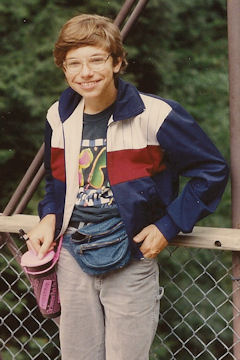

In school, that devotion to a then-20-year-old television franchise added to my reputation, but didn’t define it. I was a small kid with thick glasses and a bad haircut who got straight As and was a liability in gym class. I valued utility above fashion in all things. All that probably helped my categorization as “nerd” – not just “geek,” full-out “nerd,” to the point of my small cadre of friends being labeled the “Nerd Herd” – far more than liking a TV show. I earned that name.

I didn’t even become a computer geek until college; my only real experience with PCs before that was a single 8th grade class in which we wrote reports and created vector drawings on Macs that were obsolete even then. In the college computer lab – also mostly Macs – I became addicted to e-mail and the Web, and frequently helped out other students getting error messages or failing to print.

The vast majority of my friends there were into Dungeons and Dragons gaming, which I wasn’t, so I was an outcast among outcasts. Not that they actively excluded me – they always welcomed new recruits – but it was a bond between them that I could never fully understand. That outcast status, lonely as it was sometimes, felt more appropriate to who I was than taking up a new interest just because it was “geeky.”

That we see so much evidence of geek culture going mainstream through the window of a Web browser is not coincidence. Aside from us all creating filter bubbles around our Web experiences, the Web itself is shaped by geeky people. Not every Web programmer or blogger is into video games or British science fiction, but there’s enough overlap that it amplifies the impression that geeks are becoming mainstream. They are, but not, I suspect, as much as the Web would have you believe.

What geekdom has conquered is a fair number of, for lack of a better term, beautiful people. Picture someone fitting the negative connotation of the word “geek” and you don’t get the girl who could be prom queen if she would just let her hair down and take off her glasses. You get a pimply kid with weird proportions and an asymmetrical face. That person’s interests are irrelevant. But if hunks like Nathan Fillion and babes like Felicia Day identify as geeks, that takes away some of the identity the more traditional and less attractive geeks have built for themselves. Even when we grow up, the sting sticks with you.

I can’t say for sure that’s what Tara Tiger Brown’s experience was. Just mine. Please share yours.

Pingback: Growing up geeky John "jaQ" Andrews :: FreakyGeeky.com